|

Notre Dame's "12th Man"

Bill Stern's Favorite Football Stories, Bill Stern (1948)

The great Knute Rockne himself is the authority for this: the startling fact that a forward pass was never completed in territory defended by George Gipp - Notre Dame's football immortal. ...

George Gipp As the story is told, one day when Gipp was a freshman at Notre Dame [1916], he was amusing himself by kicking a football. Every time he punted, the ball traveled well over fifty yards. An assistant coach happened to walk by and his eyes almost popped out. Quickly he called the boy over and said, "Hey, son! What's your name and where did you learn to kick like that?" The coach rushed to Rockne to tell him the story. Rock knew how to make friends with fighting lads. One afternoon he invited Gipp to watch the team work out. Suddenly the Old Man said: "What do you think of it, son? Guess you wouldn't want to try it, it's a kind of rough game at that!" Gipp flared: "Mr. Rockne, I could run right through that varsity line of yours if I had half a mind to do it. Give me a pair of football togs and I'll show you!" Quickly he trotted back from the dressing room. Rockne lined up his team and said: "Boys, the freshmen will take the ball and a fellow by the name of George Gipp will carry it. Stop him if you can!" The whistle blew, Gipp took the ball through that varsity team like a wild mustang. Again and again he ripped the line into shreds. Finally Rockne called a halt, threw a fatherly hand around Gipp and said: "I'm convinced that for the next few years, Notre Dame is going to have great teams and that you will become one of the greatest players in the game. It's a tall order, son, but are we going to try it?" Gipp was the son of a minister - yet his style of living was hardly a model for young America. Gipp was wild and full of mischief. At heart he was a gambler. He could do more with a deck of cards than a magician. Often, he would sit in poker games with professional gamblers and win their dough. Gipp's gambling and indifference to fame when playing football almost drove coach Rockne wild with rage.  Knute Rockne Once, during an Army-Notre Dame game, Rock became horrified when he saw his team using plays that he hadn't taught them. The men were having conferences at every opportunity and were evidently making up plays as they went along. Suddenly a back who had never caught a pass in a game before shot down the field to receive a long and tricky toss from George Gipp. That play was too much for Rockne. Acting on the oftproved-theory that if there was deviltry afoot, George Gipp was at the bottom of it, Rock ordered Gipp out of the game. Rockne said sarcastically: "George, I'm sorry my offense isn't good enough for you. It's too bad you had to go to all that trouble of making up plays on the field." Often lazy, indifferent, an incurable gambler, George Gipp became Rockne's "cross to bear." Several times, Rock saved him from being kicked out of Notre Dame. But Gipp became the greatest football player in Notre Dame history and one of the greatest of all time. To play the last game of his college career, George Gipp arose from a sick bed. It was a bitter cold, wintry day. He wanted to play just once more. The stands roared for Gipp, and Rockne sent him into the game for his final appearance on a college gridiron. He returned to school sick. He was put to bed and never arose again. George Gipp in life won many football games for Knute Rockne, and in death, too, he went on winning for Notre Dame. Years after his death, Knute Rockne used Gipp's name to inspire Notre Dame elevens to scale the heighs and win incredible victories. For Rock would often begin his strange dressing-room pep talks with - the story of George Gipp. "I was with Gipp at the end, and he died in my arms," Rockne would tell his players. "I remember his last words. 'Rock,' he whispered, 'I know I'm dying. But when the going gets tough, just remind the boys that if they could - could score a touchdown for the Gipper, I'd hear about it - some place.'" There is no counting how many games George Gipp won for Notre Dame long after he was dead. On the campus of Notre Dame, George Gipp still lives. He's always "the twelfth man on the field" in every game the Fighting Irish play.

Mr. Smith Doesn't Go to Washington

The Pro Football Chronicle, Dan Daly & Bob O'Donnell (1990)

Redskins owner George Preston Marshall let a Washington sportswriter draft a player for him in 1952. The writer was Mo Siegel, who was coveing the team for the Washington Post. The player was Flavious Smith, an end from Tennessee Tech. You won't find Smith on the team's list of draftees from '52. Or the league's, for that matter. He somehow disappeared between the time commissioner Bert Bell announced his selection and the end of the draft. Therein lies the mystery of an otherwise hilarious story. Siegel ... says he pestered Marshall into letting him make the pick on the train ride to New York, where the draft was taking place. "Marshall's theory was writers didn't always know as much football as they should," Siegel says. "I told him, 'Give me a pick in a later round, and we'll see what I can do.' He didn't have anything to lose, anyway. It was very rare that a player drafted in the later rounds ever made a team in those days."

Sure enough, Marshall approached Siegel after the early rounds were done and told him to come up with the name of a player. Siegel did, and as he recalls the Redskins selected that player - Flavious Smith - somewhere between the 15th and 20th rounds. "Congratulations," Siegel remembers Marshall saying, "you've just become the first sportswriter to draft a player." "Congratulations, George," Siegel replied, "you've just integrated the Redskins." What a stunt. Marshall had a strict whites-only policy on the Redskins. Siegel hadn't known whom to draft and had turned to the Chicago Tribune's Ed Prell for help. It was Prell who'd given him Smith's name and the information that he was black. "I'm quite sure he [Marshall] thought I was kidding," Siegel says. "I'd been kibitzing with him a lot. But then he tells me the next day that he'd traded Smith, and I'm pretty sure he said to Green Bay." It's unclear what Marshall did with Smith, but he didn't trade him. The transaction doesn't show up in the Redskins' records or in press accounts of the draft. According to the Associated Press' team-by-team and round-by-round selections, no player named Flavious Smith was drafted in 1952. Yet Siegel was present when Bell announced the pick for the Redskins. What gives? We're not certain, but it isn't hard to imagine Marshall and Bell "fixing" the situation behind the scenes. The Redskins could easily have relinquished their rights to Smith and been given another pick later in the draft. No one was paying much attention then, anyway. Smith, an all-Ohio Valley Conference end as a senior, eventually signed with the Rams as a free agent. "I never heard anything about the Redskins or the draft," he says. "Two or three tems contacted me about trying out with them. I went with the Rams ..." The Rams stashed him on a reserve list in 1952, paying him a small amount to play for a semipro team. He was traded to Pittsburgh in '53 and released during training camp. He went into teaching and coaching and eventually completed his Ph.D. In 1962 he returned to Tennessee Tech, where he's now chairman of the health and physical education department. He chuckles at the suggestion he might have become the player who integrated the Tennessee Tech. Smith, you see, is white.

The Branch Rickey of Pro Football

From Myron Cope's interview with Bill Willis in The Game That Was (1970) Early in the spring of 1946, after Paul [Brown] had become coach of the Cleveland Browns, I drove over to Cleveland to ask him if there was a possibility of my playing in the new league. He told me he knew of nothing whatsoever in the league's constitution or bylaws that would keep Negroes out. He said he was going to a league meeting soon and would be in touch with me later. I felt encouraged.

Now it so happens that at that time the Canadian League was beginning to compete for American football players, and not long after I visited Paul I heard from a coach named Lew Hayman, who invited me to play in Montreal. That very year, Jackie Robinson was breaking into organized baseball in Montreal, and I had read that he was being accepted for the great ballplayer he was. So I made up my mind that if I couldn't play for Cleveland, I would play in Canada. Early that summer, in order to get ready for the season, I underwent surgery on an old knee injury and had the cartilage removed. Time was slipping by, and I had heard nothing further from Paul Brown, but Lew Hayman came to visit me and left me a plane ticket with instructions to report to the Montreal club in two weeks. It was a Sunday ... and I was just about to pack up and go to Canada when I received a phone call from a fellow named Paul Hornung, a Columbus sportswriter. He had covered the Ohio State games and thought an awful lot of me, and now he was calling from the Browns' training camp at Bowling Green and wanted me to come to camp and try out. "I can't do that," I said, "I wouldn't feel right walking into camp without being invited."

.jpg)  L-R: Bill Willis, Paul Brown, Marion Motley Hornung said, "Now wait a minute. You just get over here." He said, "You just take my word for it that you can make this ball club, and as a matter of fact, I'll stake my reputation on it." Well, I said, "Look - I have a plane ticket to go to Canada. If I go to the Browns' camp it's going to cost me expenses." Then Hornung said, "Never mind about that. You just be here." He was so insistent that I finally said okay. I phoned Lew Hayman and told him what I was doing, and he bet me a new hat that I wouldn't make the Cleveland club. Practice was just ending when I arrived in camp. When Paul Brown spotted me, he came across the field to greet me, and it seemed obvious from his manner that he had been expecting me. I imagine he'd put Paul Hornung up to phoning me. Why? I don't know why. Nor do I know if Paul knew anything about my surgery, but he asked me if I felt I could play football. "I don't know," I said. "I think so." I said nothing about my knee. I had been exercising it some, but the thing was still kind of gimpy. "Well, go get a uniform and be out here tomorrow," Paul said, and the next day, toward the end of scrimmage, he put me in on defense at middle guard. The five-man line was popular then, and as middle guard I played directly opposite the center, who on the Browns happened to be a player named Mo Scarry. He had gone over to the Browns after playing a couple of seasons in the National Football League and was very quick at snapping a football. In fact, he had the reputation of owning the fastest hands in pro football. But the first time he snapped that ball back to Otto Graham, the QB, I hit right into him and drove him into Graham and broke up the play. As a matter of fact, I broke up four straight plays. Scarry couldn't believe I was getting through him legally. He yelled, "Hey, check the offside!" ... But what I had been doing, you see, was concentrating on the ball. The split second the ball moved, or the hands tightened, I charged. And I charged him a different way every time. I would go under him, then over him. I would bang off his left shoulder, then I would bang off his right shoulder. I caught Graham every time, usually before he had even begun to pull away from center. My knee was still a little weak, but I figured I had to make the club that day. "Yes, I had better check this for offside," Paul said when Scarry started complaining. Paul got down in a crouch in the linesman's position, and he stationed one of his assistants, Blanton Collier, right behind me. The offense ran three more plays, and all three times I charged through and caught Graham. Paul called off practice and told me to see him at his office that night. He signed me to a four-thousand-dollar contract and told me to say nothing to anyone. An announcement, he said, would be made at the proper time. So that's how it all began. Although I was the first Negro player in the league, my arrival in training camp caused no commotion as far as I could tell. You see, in contrast to most professional teams, Paul had gathered most of his players from the Big Ten, and there were about six men I had played with at Ohio State. After I had been in camp for a week, as I recall, Paul announced that he had signed me, and again there was no commotion. And maybe that's why Paul decided to sign Marion Motley. He asked me one day if I would like a roommate. I said that would be nice, and he said, "Well, Marion Motley is going to be reporting." ... In the beginning I played both ways, offense and defense, and up there in the line I'd hear the opponents getting ready for Marion - especially the Brooklyn Dodgers, who had quite a few bigoted players on the team. That is, there were many players who tried to create racial tensions while playing. You would hear them yell, "Get that big black blankety-blank!" or "Look out over this way! That black so-and-so is coming around here this time." They also had some choice words for me. When they stopped Motley, they would hold him up, keep him on his feet, so they could take shots at him. They would keep coming, taking whacks at him. The first time we played the Dodgers, just about the whole lot of them piled on Marion. I started pulling guys off, saying, "Okay, boys, the play's over! Let's go!" Well, they had a five-by-five type, a guy about 260 pounds, and he wheeled around and said, "Keep your black hands off me!" I stepped back a pace in case he tried to reach me with a punch, but I was angry and I kept my hands on his shoulder pads. Before anything more could happen, some of our players - Lou Rymkus, Lou Groza, and some of the others - raced over and broke it up. Then Rymkus told me there was no point in my getting into fights and risking being thrown out of the game. He said, "If anyone gives you a bad time, you just tell us. We'll take care of him." ... I had some unpleasant moments in pro football, but the experience was much more pleasurable than unpleasant. I never had a run-in with a teammate. I did not have the problems that Jackie Robinson experienced when he broke into the big leagues. Perhaps I was fortunate that I had played with or against many of the pros in college. And don't forget, we were a Paul Brown team. It has generally been overlooked, but I think it is accurate to say that Paul Brown was the Branch Rickey of professional football. Oh yes - Lew Hayman, that fellow from Montreal who bet me a new hat I'd never make the Browns - he bought me a very nice Stetson.

Love of the Colors on the Chest From "No Matter Color You Bleed," Rick Bragg, ESPN the Magazine 8/18/14

Dicky Maegle was fast that day, his legs still fresh in the second quarter of the '54 Cotton Bowl. Maegle, the Rice halfback and future College Football Hall of Famer, took the handoff near his own goal line, turned the corner and blazed along the Alabama bench, on his way to a sure 95-yard touchdown.

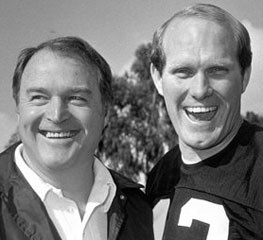

From the sidelines, Tide fullback Tommy Lewis, who'd scored his team's only points in the first quarter, turned to see Maegle racing across the midfield chalk. In one second, one never-ending second, he launched himself bareheaded and laid Maegle out in one of the most memorable tackles in college football history. The refs gave Maegle his touchdown, and Rice would eventually win 28-6, while Lewis was left to wonder forever about what he had done. He lost his composure, he would later say as a guest with Maegle on The Ed Sullivan Show, because he was so full of love for the colors on his chest that he had to come off the sideline and knock that man down.

L: Dicky Maegle, Rice; R: Tommy Lewis, Alabama The tackle lives on and on, as close as Google, or your granddaddy's memories. It is one of my favorite college football stories, not for its strangeness but because it proves something I've always believed: that no matter how much you dress it up or poke at it, college football is, at its core, a kind of beautiful chaos, something science, and certainly not people, can neither manage nor explain. ... "He grieved and grieved and grieved over that play," said Helen Lewis, who married Tommy Lewis less than two years before that Cotton Bowl. "He was a captain, you know? But people always wanted to talk about that one play." Over their long life together, they would be out to dinner and someone would say, "Oh, you're that Tommy Lewis." Later, when that person had walked on, she would tell her husband: "Tommy, I am so sorry." But he eventually became famous, for showing people what was under the helmet, for embracing how much he loved this sport and all its beautiful chaos. In 2003, when Tommy Lewis was an old man, Mal Moore, Alabama's director of athletics at the time, asked him to carry the game ball onto the field before kickoff against Kentucky, a thing reserved for distinguished alumni and VIPs. Lewis would later say he was not sure what to expect - he thought they might boo. But the fans began to wildly cheer him; he almost choked to death, he told his wife, trying not to cry. Today, after a series of strokes, he resides in an assisted living facility in Huntsville, Alabama. "He doesn't call my name anymore when I walk in the door," Helen told me. But when a teammate came into his room a few years ago, he sang out, "There's ol' No. 82." Science, maybe, can explain that, but not to Helen's satisfaction. ... Tommy Lewis could have hidden from the game all those tortured years. But, Helen told me, it was his life. A lot of people say that, but she believes, especially as a young man, it was true for him. He never stopped going to the games in Tuscaloosa, never stopped sticking out his jaw to let the whole world take a swing; only his failing health finally kept him away. Before Tommy fell ill, he and Helen went to see the cemetery plot where they would one day rest, side by side. Something made her ask: "What would you do if I had to be buried on a Saturday," on a day Alabama played? This game, Helen Lewis told me, "will break your heart." And still, for as many times as it does, for as many times as they tear it apart and put it back together, we keep on loving it. Helen, though, has not seen a Tide football game, up close, since her Tommy fell ill. "I don't go without him," she said. Imagine that, something more important.

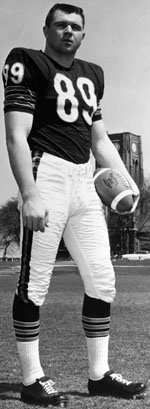

Ditka Becomes a Bear

Ditka: An Autobiography, Mike Ditka (1987)

The Bears needed a tight end. ... The players helped me a lot. Guys like [MLB] Bill George took time to show me the tricks of the trade. Playing tough and hard wasn't a problem, but I needed to know the skills involved.

When I came out of the All-Star game and joined the Bears' camp, we played the Eagles in an exhibition game in Hershey, Pennsylvania. I knew I could play against the pros by now. The only question I had about my talent was not whether I could hit with people. My question was speed. I had only been with the Bears four or five days. I had been sick and had lost weight. I didn't play the first quarter. Then Halas put me in and they hit me with a look-in pass and I ran 70 or 75 yards for a touchdown. The guy chasing me was Irv Cross and he didn't catch me. Then I knew I could play. It was my confidence builder. Since I had been sick, I couldn't wait to get into the locker room at halftime and get something to drink. A bottle of Pepsi was setting up by the fountain and it looked like it had just been opened. So I reached up and took a swig of it. I almost died. Max Swiatek, who was Halas's sidekick for years, came running over and grabbed it out of my hand. It was the Old Man's and it was half bourbon.

Teacher Extraordinaire

"Leading Off," by Dan Pompeii, SportsonEarth.com

For a time in the 1960s, Chuck Noll was the San Diego Chargers defensive coordinator and John Madden was the San Diego State defensive coordinator. They frequently would get together to play handball or racquetball or to have a bite to eat. And talk football. Madden was teaching graduate classes on football during this period. Noll was more than happy to be his guest lecturer from time to time. "He loved that," Madden says. "That was Chuck Noll - in a classroom, talking to coaches and teaching. I learned a lot about him and a lot from him then. That's where I learned pro defense, from Chuck Noll." We forever will call him a coach, but Noll, who died last week at 82, saw himself as something else. When Sports Illustrated's Paul Zimmerman asked Noll in 1980 how he wanted to be remembered, Noll said he wanted to be thought of as a teacher. "A person who could adapt to a world of constant change," Noll said. ...

Four Super Bowl victories, the most of any coach in history, merely were a byproduct of teaching well. Noll, who studied education at the University of Dayton, preached attention to details and consistency. He was very hands- on, even working with players one-on-one long after most of them had trotted off the practice field. Madden recalls Noll the coach as a deep thinker and a fundamentalist. "That's what the Steelers were all about," Madden said. "Once they had the fundamentals down, they didn't make mistakes, and then they could play aggressively. Sometimes, if you ever get an old film, just watch the footwork of Jack Ham. He was a guy I used to study all the time because he was never out of balance. His feet were always in a perfect position no matter how he moved. Those were the things that were important to Chuck." ...

L: Don Shula and Chuck Noll; R: Noll and Terry Bradshaw Noll preferred to hire assistant coaches from colleges, because he thought they usually had better teaching skills than most coaches who had been in the NFL. His appreciation of teaching undoubtedly was rooted in the fact that he had great teachers. As a guard and linebacker on the Cleveland Browns, he played for Paul Brown, who wrote the first playbook in history. He coached under Sid Gillman, the father of the modern passing game. And he was an assistant for Don Shula, the winningest coach ever. Noll would follow each of them into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Madden said Noll was a lot like Brown in that he was a teacher first, one who analyzed the game differently than most. Noll had his own style, however. He was not a yeller or babysitter. He gave his players freedom and kept rules to a minimum. He thought being rested and mentally alert was more important than putting in more time than the opposing coach. He was not one of those coaches who was unaware of the world beyond the goal posts. In fact, Noll could hold his own in a conversation about fine wine - while he was preparing dinner. He could pilot a plane, cultivate roses, sail a boat and scuba dive. He enjoyed listening to jazz and traveling, and he could talk politics or philosophy with intelligence and perspective. Noll was far from a warm-and-fuzzy new-age player's coach, though. He made Terry Bradshaw a person project and broke him down over time with tough love. Some perceived Noll as aloof and distant. He was known for a menacing glare that could hit his players harder than any linebacker. "In my time I didn't see him hug a player ... but he still loved his players," Steelers great Joe Greene said ... "But I watched him, and I saw him show his appreciation for his players and for his team in a very quiet and subtle way." ...

"I'm Gonna Buy the Dallas Cowboys."

"Jerry Football," by Don Van Natta Jr., ESPN the Magazine 9/15/2014 It has become football lore that Jerry Jones was inspired to buy the Cowboys after waking up with a five-alarm hangover during a fishing vacation in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico. After downing too many margaritas the night before with his 23-year-old son, Stephen, Jones - by then an oil and gas baron worth more than $100 million - stayed behind at the hotel and, in a day-old newspaper, stumbled upon a brief story: "Bum Bright to Sell the Dallas Cowboys."

"Well, I wasn't up to par," Jones says. He called the office of Cowboys owner H.R. "Bum" Bright and said, "You don't know me from Adam. My name's Jerry Jones. But if I live, I'm gonna come straight back to Dallas and buy the Dallas Cowboys." Jones returned home on the next plane and quickly became the team's top suitor. A fierce negotiator, Bright decided the final $300,000 separating him and Jones would be determined by a coin flip. (Jones called tails and lost.) The morning after they shook hands on the $151 million price tag. Bright called Jones at home and told him a group had just offered to buy the Cowboys for $10 million more. Jones said no to a quick $10 million profit. "I don't think Jerry would have sold the Cowboys for $100 million more," says friend Sheffield Nelson.

L: Arkansas G Jerry Jones with his future wife, Gene; R: Jones at his first press conference as owner of the Cowboys; Outgoing GM Tex Schramm is in the background in the dark suit. Bright had come to despise Tom Landry, the legendary Cowboys coach who had won two Super Bowls in 29 years but whose ideas had grown stale and whose team reflected it: Dallas finished 3-13 in 1988, months before Jones bought the club. Many fans in Dallas wanted Landry out, and Bright offered to fire him before selling the Cowboys to Jones. Jones insisted he do it himself because, he says, "I needed to man up."

Hours after firing Landry, Jones introduced himself to the Dallas media as the team's new majority owner. "This is Christmas to me," Jones, then 46, told reporters. He spoke more about hiring old friend Jimmy Johnson, the University of Miami coach with a 52-9 record and a national title, than about the legacy of Landry. "I intend to have a complete understanding of contracts, jocks, socks and TV contracts," he said. Now Jones admits his tin-eared exuberance and lack of proper respect paid to Landry and Tex Schramm - the team's original president and GM who stood during the news conference while Jones sat - were unbecoming. The showing caused him to stumble with practically everyone in Texas, especially the media. "Jones was completely lost," Galloway, the Dallas Morning News columnist, wrote then. Aghast at the criticism, Pat Jones called his son. "Jerry," Pat said, " I don't care if it works or not, you gotta make it look like it does. You use mirrors, smoke screen or something, because if you don't, you'll be known as a loser the rest of your life."

"Yoda of the Air Raid Offense"

Kevin Van Valkenburg, ESPN the Magazine (9/29/14)

Who is the best college football coach of the past two decades? It's clearly Alabama's Nick Saban ... But the most influential coach of the past 20 years? That'd be Hal Mumme. He wasn't the only one to drag college football out of its ground-and-pound dark ages. But as Kentucky's coach in the late 1990s, he is the one who brought video game offenses to the SEC, the game's motherland. And it was there that football changed forever. ...

In NCAA history, there have been 79 times a quarterback has thrown for at least 4,000 yards in a season; 65 of them have come since 2000. Mumme-influenced offense are so pervasive, in fact, that Auburn defensive coordinator Ellis Johnson says, "It's to the point now where the three or four teams we play a year that line up in two tight ends and a fullback are harder to prepare for. ..." All this raises a rather obvious question: Why the heck did a godfather of modern college football coaching, a man with a career record of 137-118-1 through Week 2, just take a gig at an NAIA school that went 3-8 last year and plays its home games in a high school stadium? ... Like countless Texas boys before and since, Mumme grew up enamored with football in the Lone Star State. In 1979, after an uneventful college career at Tarleton State and three years as an assistant coach at Moody High School, he interviewed for his first head-coaching job at Aransas Pass High. ... He wasn't the most experienced candidate. He didn't have a prepared speech or even a playbook. But he did have the ability to sell himself as an agent of change. He told Aransas and every team that would interview him that he had no use for three yards and a cloud of dust. His team was going to be fun to watch. It would throw the ball all over the field and get off plays as fast as possible. ... After just a year, Mumme left Aransas Pass to be a passing coach at West Texas State. By 1982, he had climbed another rung up the coaching ladder when he joined UTEP as offensive coordinator at the age of just 29. It was there that the artist found his canvas. The downside was that coach Bill Yung's teams were so short on talent that UTEP won just seven games in the four years Mumme was there. The upside was that UTEP was in the Western Athletic Conference with Brigham Young and had access to the Cougars' game films. "They were splitting three and four wide receivers out on every play," Mumme says. "I didn't know what LaVell Edwards was doing, but I knew I wanted to do that." Mumme still isn't sure why Edwards' innovative, spread-the-field attack didn't prove more influential at the time. Maybe other coaches assumed BYU's system was too hard to teach, or that it succeeded only because the Cougars were using older, more mature kids back from Mormon missions, Mumme says. In any event, when the entire UTEP staff was fired in 1985, Mumme decided to head back to the high school ranks, convinced it was where he'd finally have the freedom to build on what he'd learned watching BYU. ... He broke out his BYU film and promised the kids at Copperas Cove that "we were going to take what LaVell was doing and put it on steroids." First, he put his best athletes at quarterback and wide receiver. Then he drastically widened the splits of his offensive line - a radical idea at the time. Practices were short. No Oklahoma drills, ever. And he might call the same play (one of only three the team would learn) 50 times in a row, mixing up only the formations. ... It worked. His first season, the team became an offensive juggernaut and knocked off two of central Texas' powerhouse football programs .... In 1989, Iowa Wesleyan -- an NAIA school with just 800 undergraduates -- hired Mumme ... He cobbled together most of his staff on a minuscule budget but struggled to find an offensive line coach for $12,000 a year. "I had two people apply," Mumme says. "One was offering to bring his gang with him from Los Angeles, and the other was Mike Leach."

Hal Mumme and Mike Leach In finding Leach, an alumnus and fellow acolyte of BYU, Mumme stumbled upon the Paul McCartney to his John Lennon. Neither one of them gave a damn about college football's hallowed traditions. ...On the field, no concept was too goofy. In addition to wide splits, Mumme and Leach decided to do away with three-point stances entirely, figuring (correctly) that it would help their offensive line get in position to pass-block that much faster. They decided to run every play out of the shotgun, which they predicted (correctly) would help the quarterback better see the field. ... Every team had a two-minute offense; Mumme and Leach just wanted to employ theirs two minutes into the game. And in their minds, the quarterback couldn't snap the ball fast enough. ... In their three years at Iowa Wesleyan, the Mumme and Leach show went 25-10 and led the nation in passing once and finished second twice.

When Valdosta State came calling in 1992, Mumme and Leach took their now fully formed air raid act to Georgia, and they tore up the Division II NCAA record books as well, going 40-17-1. "We knew we were changing the game," Mumme says. "We just weren't sure if anybody else was going to change with us." Tim Couch came to the University of Kentucky in 1996 as one of the most prolific high school quarterbacks ever ... But coach Bill Curry had him splitting time and running the option. When the team started 1-6, Curry was fired. Seven games into his first year, the Wildcats' best prospect ever was all but gone.

Hal Mumme and Tim Couch Wildcats athletic director C.M. Newton asked Couch to think about staying. There was this coach at Valdosta State he wanted to grab. He told Couch: I want someone who is going to be Rick Pitino on grass. I think I've found him. Fast-forward to the quarterback's first meeting with Mumme. "He says, 'You're going to throw the ball 55 to 60 times a game,'" Couch recalls. "That's all I needed to hear. But we all had question marks. We thought, 'This might work when you're at Valdosta State or Iowa Wesleyan, but not in this conference against these kinds of defenses.'"

Which is why, in retrospect, Kentucky's first game under Mumme in 1997, against state rival Louisville, feels like the first tremor of an earthquake. Couch threw for 398 yards and four touchdowns in a 38-24 win. ... Three weeks later at Indiana, Couch tied an SEC single-game record with seven touchdown passes. He threw for 355 yards in an overtime victory against Alabama, the first time Kentucky had beaten the Crimson Tide since 1922. "Early on, it was easy," Mumme says. "No one knew how to defend it." Other coaches started paying attention. Urban Meyer, then the wide receivers coach at Notre Dame, and Sean Payton, then the quarterbacks coach for the Philadelphia Eagles, were among those who made the pilgrimage to Lexington to see what this lunacy was about. "People thought we were nuts," Mumme says. Mumme's final season at Kentucky was marred by scandal and infighting. ... Though Mumme wasn't implicated specifically, he was forced to resign from Kentucky in 2001 when it came to light that his recruiting coordinator had sent money to a high school coach in Memphis. ... But then a crazy thing happened. As Mumme moved down the coaching ladder -- short gigs at Southeastern Louisiana, New Mexico State and D2 McMurry -- his disciples installed versions of his air raid offense at schools around the country, plugging in better athletes and racking up big stats and victories. Leach taught Mark Mangino the air raid offense at Oklahoma, and the following year the Sooners won a national title with it. Leach, now the head coach at Washington State, added his own wrinkles to the air raid at Texas Tech and passed on pieces of it to Sonny Dykes (Louisiana Tech, California), Art Briles (Houston, Baylor) and Dana Holgorsen (West Virginia) ... Kevin Sumlin (Texas A&M) became friends with Mumme in the late 1990s at Mumme and Leach's annual offseason coaches gathering, even though he was then just an assistant at Minnesota. Sumlin added his personal touches as an assistant coach at Oklahoma under Bob Stoops -- more vertical routes and letting his quarterback run. ...

Mumme, meanwhile, has found contentment at Belhaven. He enjoys the simplicity of working small miracles. ... I'm listening to Mumme captivate 40 high school coaches with his own wild stuff. In a few months, he'll kick off his inaugural Belhaven season with two straight victories, outscoring opponents 76-20. But at the moment, he's enjoying his role as the nutty professor. "Let me diagram some plays here," he says. "I love this play. This is called the mesh. I once called this 53 consecutive times in a game." And as he takes the cap off his Sharpie, another generation of coaches starts scribbling.

Al Davis Goes After Sean Payton Parcells: A Football Life, by Bill Parcells & Nunyo Demasio (2014) After the 2003 season, Raiders' owner Al Davis needed to hire a new coach. He had his eye on Bill Parcells' QB coach with the Dallas Cowboys, Sean Payton.

Having played a key role in helping his mutual friends consummate an improbable marriage in Dallas, Al Davis took special note of the team's turnaround. The Raiders boss was particularly impressed with Quincy Carter's progress in an offense lacking a top runner or a first-rate wideout. So on firing his head coach, Bill Callahan, after a 4-12 season, Al Davis gained permission from the Cowboys to interview their top two offensive coaches: Mo Carthon and Sean Payton. Despite preferring to keep thm, Parcells felt compelled to let his assistants pursue a head-coaching opportunity, and even recommended the duo to his longtime consigliere.

Bill Callahan happened to be Sean Payton's friend and ex-Eagles colleague, but only two years removed from being demoted as Giants offensive coordinator, Payton was thrilled by Davis's interest. One of five candidates discussing the head coach opening with the Raiders chief in early January, Payton arrived at the team's headquarters in Alameda, California, with a bad case of the jitters. A few moments before meeting pro football's eminence grise, the forty-year-old coach walked into the bathroom and took three deep breaths while saying to himself, "I belong here. I belong here. I belong here." In mid-January Payton was the only candidate flown back to Oakland for a second round of interviews with Al Davis and personnel executive Mike Lombardi that spanned four days. By the end of Payton's trip, Davis all but officially offered him the job. Despite his inclination to accept, Payton needed to fulfill his promise to discuss the matter with his wife.

Heading to the airport for a flight to Dallas on Tuesday, January 20, Payton checked his voice mail, which included three messages from Parcells bent on finding out his quarterbacks coach's decision firsthand. As Payton walked toward his flight gate a TV monitor airing ESPN showed his face next to the Raiders logo while reporting that he was set to sign a four year deal with Al Davis. Later that night Beth Payton expressed reluctance to her husband, but after sleeping on it, Sean Payton awoke early in the morning aching to be a head coach. After persuading his wife, Payton purchased a black suit and silver tie - Raiders colors - in anticipation of his introductory press conference. He also contacted some coaches to gauge their interest in being part of his imminent new staff.

The switch to the Raiders seemed so inevitable that Dallas's equipment manager cleaned out Payton's locker, but when he arrived at his office the next day, Payton checked in with three head-coaching friends who had ties to Al Davis: Carolina's John Fox, Tampa Bay's Jon Gruden, and Bill Callahan ... After Payton heard their takes, he received a phone call from Parcells. "Listen, Sean, I want to talk to you for a minute like you were my son, not like I'm the head coach and you're my assistant. These other people that you're close to in the industry: what do they think you should do?" Bill Parcells had described Sean Payton to Al Davis as being energetic and driven with an unusually sharp offensive mind. But in attempting to dissuade his quarterbacks coach, Parcells told Payton that he needed more grooming. A few minutes after Payton hung up, he received a call from Jerry Jones requesting his presence at the owner's mansion in Highland Park. When Payton arrived, the two went into Jones's library. During their conversation the owner focused on how much the organization values its quarterbacks coach. By the end of the get-together, Payton's desire to join the Raiders had evaporated. Driving home, Payton called his wife about his change of heart, eliciting tears of delight. Then he telephoned Parcells about his final decision, followed by a call to Jerry Jones. The next morning, minutes after Payton arrived at his office, Stephen Jones walked in with a new contract; it included a $500,000 raise, part of a three-year deal worth $3 million as an assistant head coach keeping the same duties. After Al Davis found out, he dialed Bill Parcells to complain. "Why didn't you just tell me you wanted to keep him?" Davis hired Dolphins offensive coordinator Norv Turner for Oakland's lead job, and Parcells was delighted about keeping Maurice Carthon, too.

|